Sustainable Livelihoods Series: Achiote Harvest in Ecuador

05/10/2016

This is the first article in our Sustainable Livelihoods series, exploring NCI’s work with communities to develop new sources of income based on the sustainable use of natural resources in and around the areas we’ve helped these communities protect. We have seen community incomes increase and deforestation decline as a result of our efforts. Here, we explore a pilot project in the Ecuadorian Andes.

Indigenous Shuar boy with achiote paint. (Photo Credit: Juan Carlos Valarezo)

In early April, NCI-Ecuador staff members visited Santa Cecilia in Ecuador’s Zamora Chinchipe province for the second achiote harvest of the year. Achiote (Bixa orellana) is a fast-growing, shrubby tree that is native to South America. Its seeds are used as a spice and food colorant, and it is culturally significant to the indigenous Shuar people, who use achiote (ipiak in the Shuar language) to make red paint for their faces and bodies.

Achiote capsulas after harvesting.

Achiote as a sustainable livelihood and conservation tool

NCI is developing achiote as a sustainable livelihood project in Santa Cecilia and neighboring villages in the Jambué Valley. Projects like this one promote alternatives to unsustainable land uses – such as clear-cutting for cattle pasture. A primary goal of this pilot project is to help local families diversify their household income by selling achiote.

Achiote cultivation can coexist with conservation, as it can be planted on abandoned cattle pastures and doesn’t require cutting down the additional forest. Not only can achiote and native forest exist side-by-side, but with this project, families are reclaiming and re-using land in this valley.

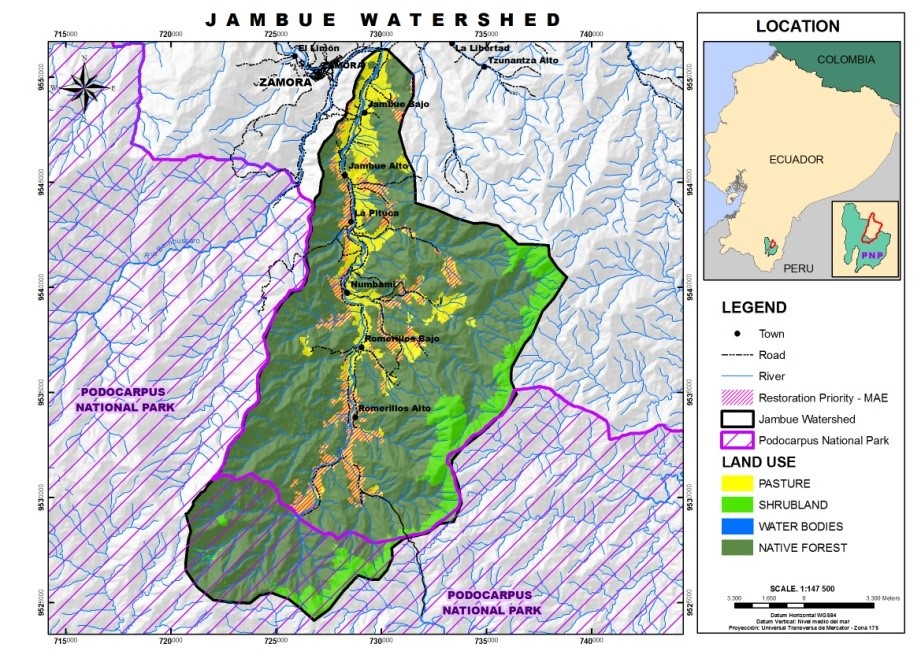

Ecuador’s Ministry of Environment has identified the red hatch marks (approx. 4,200 acres) as areas for reforestation. Santa Cecilia is between La Pituca and Numbami.

The regional conservation context

The Jambué Valley – like Podocarpus National Park, which surrounds it on three sides – is extremely biodiverse. The tropical Andes (which span much of Ecuador) host one-sixth of the world’s vascular plant species on less than 1% of the world’s land mass. Podocarpus National Park, in turn, has the most endemic plants of any protected area in Ecuador. In other words, this is the world’s epicenter of plant diversity.

Jamboé Valley’s specific location on the landscape is important. It’s an unprotected area jutting into the northern side of Podocarpus National Park (see map above). Our achiote project, with its goals to prevent further deforestation and to restore native forests on degraded lands, is critical to maintaining habitat connectivity between the Jamboé Valley and adjacent areas within the national park.

Ecuador’s Ministry of Environment has identified 4,200 acres in the Jambué watershed, mostly current or former pasture, where native forest restoration would be appropriate. In other words, there is ample land here for NCI to expand this pilot project for significant ecological and economic impact in the valley.

Amada Macas, one of four achiote producers in Santa Cecilia. (Photo Credit: Matt Clark)

Amada and Elisa Macas, two producers in Santa Cecilia

There are four producers in Santa Cecilia (15 total currently in NCI’s achiote project), but NCI staff members spent the morning with two sisters, Amada and Elisa Macas. They are Saraguro, a sub-group of the Kichwa, one of Ecuador’s 13 formally-recognized indigenous nationalities. In search of cultivable land, Amada and Elisa’s parents emigrated from the town of Saraguro to Santa Cecilia before Amada and Elisa were born.

The economics of achiote

NCI staff were particularly interested in learning about the economics of achiote: why did Doña Amada and Doña Elisa choose to plant achiote and how does it fit into their overall livelihood?

They learned that Amada and Elisa planted achiote seedlings in July 2014, and between the two of them, they have 1,350 plants on three acres. They harvested their first capsulas (seed pods) in February 2016. It’s remarkable that these plants have grown eight to ten feet in just 18 months, and that 25% of their plants are already producing fruit.

Achiote buds and flower. (Photo Credit: Matt Clark)

The Santa Cecilia producers currently sell their achiote in the capsulas (which helps preserve the seeds prior to processing) to Lojano Spice Industries (ILE) for 30 cents a kilo. For their first harvest in February, Amada and Elisa sold 81 and 60 kilos, respectively. Their second harvest was a bit less: 56 and 44 kilos. Each harvest took the better part of two days, for which they made between USD $13 and $24 total, or between $6.50 and $12 for each day’s work. In comparison, the local rate for a day laborer is $15 with three meals provided.

The challenge for producers is that achiote capsulas don’t ripen simultaneously for the first four years after planting. At any given time, an individual plant can have buds, flowers, and both immature and mature capsulas. This makes harvesting inefficient. It also means harvesting up to four times a year. Reportedly, the plants begin to synchronize fruiting during their fourth year, which would likely make harvesting more efficient. The achiote plants also reach full productivity at this time, producing an estimated annual average of 4.8 kilos of capsulas per plant. The plants continue to be productive for twenty years after initial planting of seedlings. For the sisters, gross revenue per hectare at full productivity could amount to $1,620 annually (1,125 plants per hectare X 4.8 kilos per plant X 30 cents per kilo).

The initial costs to establish an achiote plantation are significant for these families: about $3,500 per hectare. In most cases, these start-up costs have been heavily or fully subsidized by NCI. NCI also is providing technical expertise and training in plant establishment, maintenance, and harvesting.

And, achiote plants require periodic weeding and pruning with estimated annual labor costs of about $100. Transport costs to the weigh station and storage facility also need to be factored in.

At this point, Elisa and Amada are reserving judgment as to how financially viable achiote will be for them. Currently, on an hourly basis, they would be making as much or more as day laborers. But that assumes that other work is consistently available, which it isn’t. And the achiote isn’t yet fruiting in synchrony or at full productivity, both of which should significantly influence the economic calculus for the producers.

Elisa with traditional Saraguro crocheted table piece. (Photo Credit: Matt Clark)

How achiote compares to other sources of income

So what else do Amada and Elisa and their families do to generate income, and how does it compare to achiote? Until recently, Elisa’s husband had been working for the Chinese hydroelectric project under construction about 25 km away, making about $16 a day. Elisa cited a lack of other work as a primary reason for planting achiote. “Estamos sin trabajo (we are without work),” she said.

Elisa has some beef cows about two hours walk from Santa Cecilia. She views her cows as a savings account, a place to park her money until she needs it.

A cow purchased for $250 can be sold for $500 to $600 after 18 months. In the meantime, a cow requires about 1.5 hectares (a little over 3 acres) of pasture. In other words, a beef cow generates $111 to $156 of gross revenue per hectare per year, an order of magnitude less than the $1,620 per hectare per year that achiote could generate. A hectare in Santa Cecilia sells for between $1000 and $1500 and rents for $150 a year. Given those land costs, there would certainly be an incentive to find the most efficient and productive land use. That said, beef cows may be less labor intensive than achiote. Elisa checks on her cows every two weeks.

In terms of other activities, Elisa crochets traditional Saraguro table coverings, which she hopes to sell. The community recently cleared a path to Cayamuka, a unique hill near Santa Cecilia, which they hope someday might become a local tourist attraction where they can promote traditional Saraguro cuisine like cuy (guinea pig) and chicha de jora (a low-alcohol corn beer, fermented in large clay jars). They have not had any tourists yet.

A Santa Cecilia resident harvesting achiote. Note the town in the background. Most of the deforestation in the picture is cattle pasture. (Photo Credit: Matt Clark)

Remaining questions

This is a pilot project, and as such, there are a number of unanswered and partially-answered questions that NCI is still investigating. NCI staff are collecting data and analyzing the various factors to determine if and how this project would be replicable at a larger scale. As demonstrated by the map above, there is a lot of potential lands in which to expand this project. The scalability of the project will determine how broadly NCI and Jambué residents are able to restore degraded lands and transform the local economy to a more sustainable basis.

There are questions on the supply side. What are the barriers to entry for a potential achiote grower? Clearly, there are significant start-up costs, but does lack of familiarity and knowledge play a role too? Is the type or timing (seasonality) of the work a factor that influences the decision to plant achiote? Related to this, are there tools that NCI could develop to make replication more viable (for example, how-to manuals or a business plan)?

There are questions too on the demand side. For example, would buyers be willing to pay a premium price for environmentally sustainable achiote? This could be a factor in ensuring that it’s profitable for the producers.

NCI will be revisiting these questions as we contemplate the future of this project.