The true meaning of “spotting a jaguar”

03/02/2023

“La abuela”, a female jaguar that had not been seen for almost 10 years, made a hopeful appearance on the outskirts of Ejido of Munihuaza, in Sonora, Mexico.

The inhabitants of Ejido of Munihuaza had not seen jaguars on their land for a long time. The increase of livestock and open-range grazing in the area had significantly reduced jaguar habitat due to continuous conflict between the animal and ranchers who take action out of fear that the cat would hunt their livestock.

“There is a lack of community awareness,” says Gilberto Díaz, a Nature and Culture technician in Mexico, “there is a lack of knowledge about the importance of caring for the jaguar’s habitat since its survival is closely tied to the integrity of the ecosystem,” he points out.

Ejido de Munihuaza is in the protected area of Sierra de Álamos-Río Cuchujaqui, in northwest Mexico. There, the thorny scrub, pine and oak forests, and riparian vegetation intermingle, creating an excellent biodiversity corridor that is home to hundreds of species of flora and fauna, among them the jaguar and other felines such as the puma, and the ocelot.

Thus, in an effort to protect the northernmost corridor of jaguar habitat, Nature and Culture joined the “Borderlands Linkages Initiative”, a project led by the Wildlands Network involving eight organizations from Mexico and the United States. This initiative includes monitoring the activities of the jaguar as well as assessing the restoration needs in the Sonora region.

Nature and Culture chose to monitor the cat in Ejido de Munihuaza because it is adjacent to the Monte Mojino Reserve, a private reserve of the organization, and because it provided an opportunity to collaborate with locals on community projects with an environmental focus. “For us, it was essential that community members of Ejido participate in the activities,” says Gilberto. This is how he, Anselmo Palomares, Alejo Palomares, and José Bojórquez formed the monitoring team and worked together from August 2021 to April 2022 in the training, installation, and maintenance of camera traps to make the mythical jaguar visible.

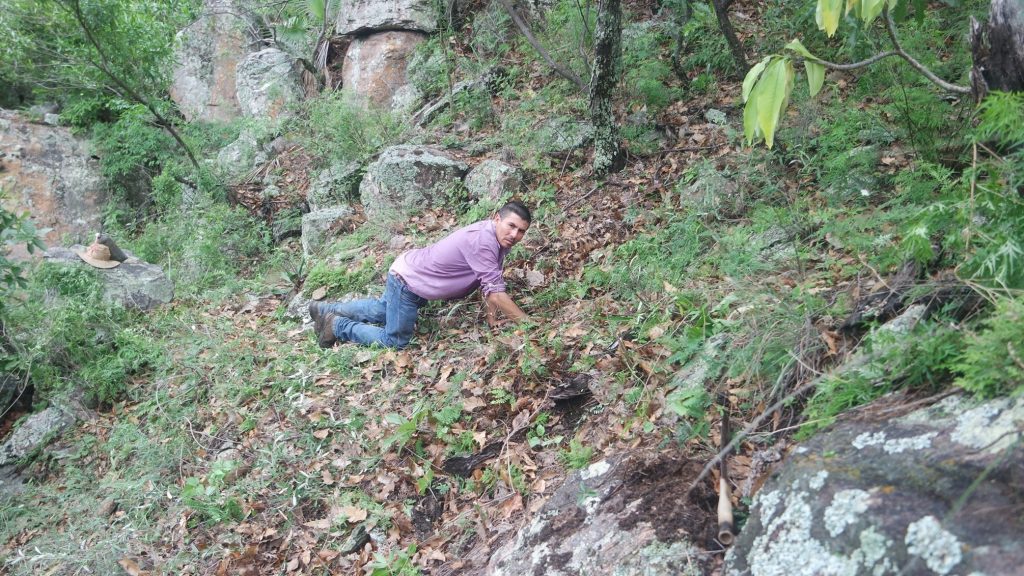

In total, they installed 22 camera traps that covered 90% of Ejido. For the location of the monitoring stations, the team surveyed the area, cleaned it, and placed each camera strategically to avoid “junk images”, that is, photos activated by the wind, leaves, etc. Díaz highlights that, although it was the first time that José, Anselmo, and Alejo carried out wildlife monitoring, they took to the task quickly. “They were coming up with ways to make sure the camera traps worked, like walking like a jaguar,” he says.

The installation work was arduous, not only because of the irregular topography of the region that goes from sea level to almost 4,000 feet above sea level but also because of the summer season. “We worked from 5 in the morning to noon and from 3 in the afternoon to 6 in the afternoon, avoiding the hottest hours,” says Díaz. They also helped themselves with mules to be able to travel long distances and reach the objectives of the day. Gilberto warmly remembers that the families of the community made him feel at home, offering him lodging and food when the days did not allow him to return home.

Now all that was left to do was wait. The park rangers had to periodically monitor each of the monitoring stations, review the photographic record of the cameras, download the data, and delete it before reinstalling the cameras. Each of the rangers received economic compensation for this activity contributing to improving their home life. “The support is noticeable at the table,” said one of them, “this support allows us to buy gas,” added another.

Months passed and the jaguar did not appear in the image. They saw, among other species, deer, pumas, squirrels, and many cows, but the characteristic black spots of the feline did not appear on the recordings. Every day of monitoring, the team looked for the jaguar enthusiastically, but as the project’s closing approached, it still had not appeared. It was not until the last shift that they saw her, in one of the cameras located in the best-preserved area of Ejido.

With the recordings, the Northern Jaguar Reserve confirmed that it was not only a jaguar but that it was the second oldest female recorded in the region, an individual that had not been seen in the area since 2013. “Seeing a jaguar is very important since it is an indicator of a healthy ecosystem. But seeing a female jaguar brings hope since it means that reproduction is possible”, explains Gilberto. The people of Ejido were filled with emotion upon hearing the news and collectively agreed to name her “la abuela” or grandmother, as a symbol of wisdom and hope for the community.

Thanks to the monitoring of the species, the community of Ejido de Munihuaza understood the importance of protecting the habitat of species such as the jaguar. But the effort must continue, as Díaz mentions, “It is essential to strengthen monitoring strategies and disseminate information so that the people of the communities take ownership and take care of what is theirs”, because “conservation is not only about protecting habitat, it is also the social environment”, he concludes.